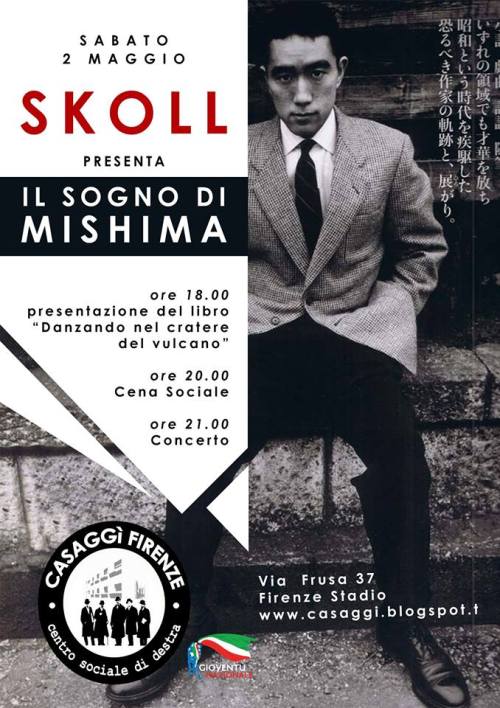

Mishima ed il Movimento Studentesco: Zengakuren

Mishima ed il Movimento Studentesco: Zengakuren

Testimone della città di Tokyo in fiamme, dopo essere stata bombardata dai B-29 (dell’USAF, aereonautica statunitense), con l’uccisione di decine di migliaia di cittadini, Mishima reagì con la gloria, come fosse qualcosa di epico e maestosamente colorato. L’imperatore fu costretto a dichiarare la resa incondizionata. Le nazioni alleate posero tremende ed umilianti condizioni al Giappone. Il primo gennaio 1946 Hirohito fu obbligato a negare pubblicamente la propria origine divina, anacronismo per la materialistica mentalità occidentale, ma intollerabile per i veri giapponesi. Niente discendenza dalla dea del sole Amaterasu per il Mikado, sancita dal famigerato articolato numero 9 della Nuova Costituzione, promulgata il 3 novembre 1946, che imponeva al Giappone la rinuncia alle sue prerogative militari. La concessione perpetua dell’isola di Okinawa come gigantesca base U.S.A.. L’America non desiderava che un esercito giapponese autonomo difendesse il Giappone. Sacche di resistenza, specie a sinistra, a tali imposizioni furono placate dal governo con la favola della difesa della Costituzione, rafforzando la sua politica con vantaggi concreti senza onore. Per il Jieitai fu una ferita mortale. Il Jiminto (Partito Liberale Democratico) ed il Kyosanto (Partito Comunista), che insistevano sull’importanza della politica parlamentare, spazzarono le possibilità di ricorrere a metodi non parlamentari. Il Jieitai da figlio illegittimo della Costituzione divenne ‘’Esercito di Protezione della Costituzione’’, strumento di politici intercambiabili e degli interessi di partito.

Lo spirito del samurai virile era umiliato ed il Tate No Kai vi si ribellò, mentre nel Jieitai nessuna voce virile si levò contro l’ordine vergognoso del ‘’Difendete la Costituzione che vi rinnega!’’, silenzioso contro la logica distorta della Nazione. Il Jieitai auto ingannato ed auto dissacrato, privo di anima e spirito, limitato ad un controllo civile, fu accusato dalla sinistra di esser mercenario dell’America. Il valore dello spirito sulla vita, non era la libertà, la democrazia, ma il Giappone, con la degenerazione morale e il decadimento spirituale dei nipponici. Interpretazioni legali opportunistiche facevano dimenticare il problema della difesa, per legge il Jieitai era incostituzionale. Il Jieitai era stato oggetto di un inganno malvagio, aveva sopportato il disonore della Nazione dopo la sconfitta. Un’abnorme forza di polizia, non esercito nazionale armato senza sapere a chi dichiarare fedeltà. L’esercito proteggeva la storia, la cultura e le tradizioni della Nazione, la polizia difendeva la struttura politica. Il Giappone del dopoguerra seguì l’infatuazione della prosperità economica, dimenticando i grandi fondamenti della nazione, perse lo spirito nazionale, correndo al futuro, senza correggere il presente, piombato nell’ipocrisia e precipitato nel vuoto spirituale.

Il gioco della politica interna dissimulò le contraddizioni, mentre sprofondava nell’ipocrisia e nella bramosia di potere. La difesa dei particolarismi e degli interessi personali. Paesi stranieri si erano arrogati i piani riguardanti i prossimi cento anni della Nazione; l’umiliazione della disfatta nascosta per non essere cancellata, la profanazione della storia e delle tradizioni del Giappone, avrebbe richiesto il sacrificio della morte. Dagli anni ’50 sgretolato, anche psicologicamente, dalle bombe normali che distrussero il 75% delle città e le atomiche ipercriminali, l’Impero del Sole Levante fu deformato e riconfigurato nel secondo dopoguerra dagli U.S.A. a propria immagine e somiglianza. Il periodo post-bellico e post bomba atomica, gli orrori sociali della ricostruzione, l’asservimento economico, militare e culturale agli Stati Uniti, gli anti-corpi libertari, sessuali e ‘’criminali’’ concepiti dalle nuove generazioni, regolarmente e psicoticamente represse. Il Giappone era svenduto al ‘’modus vivendi’’ dell’occidente statunitense; al mito del ‘’Nuovo Giappone dei transistors’’. Il motto di Mishima era: ‘’Ciò che trasforma il mondo non è la conoscenza ma l’azione’’, ‘’In nome del passato abbasso l’avvenire!’’.

Cosciente della vita e della cultura integrale fu chiamato al sacrificio di sé stesso per difendere la continuità stessa di questa vita. ‘’Nella limitatezza dell’umana vita, io scelgo la vita dell’eternità’’. Il suo suicidio futuro fu esaltazione poetica della vitalità e grandezza patriottica dello scrittore, della lealtà e fedeltà all’Imperatore ed ai valori tradizionali da questo incarnati, spinta agli estremi livelli, dovere primario di ogni giapponese. Un romanticismo ridondante sul tema della Seconda Guerra Mondiale e il Giappone, in parallelismo con D’Annunzio. Per i giapponesi di ogni tendenza politica, l’esperienza bellica era un innegabile punto di riferimento esistenziale e politico. La sconfitta in guerra era un fattore comune ed il turning point più rilevante del Novecento. Immane esperienza con un indicibile senso di felicità , l’epoca del ‘’Tenno kai Banzai’’ (‘’Viva l’imperatore’’) dei piloti kamikaze era perduta, per cui il ‘’senso di felicità’’ dell’adolescente Mishima che aveva intravisto la guerra nella forma di una ‘’luce di lampo’’, con la sconfitta, naufragò miseramente. Mishima era cresciuto in un’atmosfera di magnifico apprezzamento per la morte, che portava al militarismo romantico della metà e della fine degli anni ‘60. Si avviò a vivere nel dopoguerra ‘’un’epoca fatta di finzioni’’, ‘’un invecchiamento in tutt’armonia’’, venticinque anni ‘’incredibilmente lunghi’’ per poi far vibrare con acciaio e sangue, il cuore degli uomini, lo scorrere della storia.

Nel mondo si sviluppava il movimento studentesco; l’Occidente viveva l’era turbolenta, viva e creatrice degli anni ’60 e ’70 attraverso le sue proteste e i suoi movimenti radicali, con la Guerra del Vietnam come principale obbiettivo della rabbia degli attivisti. Oriente, Cina di Mao e Guardie Rosse divennero fonte d’ispirazione per i Weathermen ed altri gruppi radicali occidentali. L’origine e l’ascesa del gruppo radicale dalla nascita dell’attivismo studentesco in opposizione alla ratifica dell’ANPO, Trattato di Reciproca Cooperazione e Sicurezza tra Giappone e Stati Uniti firmato nel maggio 1960, sotto il governo del Primo Ministro Nobusuke Kishi, con cui si sancì, una sudditanza del Giappone agli U.S.A., dietro il paravento della collaborazione militare, dato che il Sol Levante fornì basi militari agli americani e confermò la rinuncia ad ogni intervento bellico. Gli U.S.A. si impegnavano a garantire al Giappone la loro protezione militare. I giapponesi, feriti nel loro orgoglio, reagirono violentemente: si registrarono disordini, le prime proteste e lotte contro il supporto giapponese agli U.S.A. durante la Guerra del Vietnam, resistenza che sfiorò la rivolta. Nessun suicidio rituale per protesta dai generali, quando il Trattato di Antiproliferazione Nucleare, che concerneva i piani a lunga scadenza della politica nazionale, identico al Trattato ineguale del 5-5-3, di sicurezza nippo-americano, il Giappone offriva basi militari agli U.S.A. e confermava la rinuncia alla guerra. Mishima si schierò subito con i rivoltosi.

Fino agli anni ’60 Mishima si era ritenuto di sinistra, contattato dal JCP (il Partito Comunista) per arruolarlo come membro negli anni ‘50. L’amico di Mishima, Kobo Abe, eccellente scrittore, era un membro del JCP ed era stato espulso dal partito per anticonformismo. Mishima aveva rappresentato il disagio dei valori, nella società giapponese che si stava americanizzando, condannata a vivere eternamente il suo dopoguerra; il Giappone non si riconosceva più, abbandonato, corrotto. Il romanzo ‘’Dopo il banchetto’’ segnò il suo ingresso, vibrante e violento, in politica. Stigmatizzò duramente il mercanteggiamento elettorale a cui erano dediti i politici ed i costumi dell’alta borghesia.

Conosceva i meccanismi e gli interessi dei partiti. Scopriva un mondo in febbrile e tumultuosa agitazione fuori di sé, percorso da fermenti che indicavano la volontà di superare il dopoguerra. Dimostrazioni scoppiarono in Tokyo, sotto lo striscione del Zengakuren o Zen-nihon gakusei jichikai (Federazione dell’Autogoverno Studentesco del Giappone o Lega delle Unioni degli Studenti di Tutto il Giappone), un sindacato nazionale studentesco giapponese , associazione estremista di studenti marxisti-leninisti, sorta nel 1948 dall’unione di circa centinaia di migliaia di studenti universitari di estrazione non solo marxista ab origine, i quali, come espressione del malcontento, protestavano contro l’aumento delle tasse d’iscrizione ai corsi universitari ottenendo simpatie tra la popolazione nelle agitazioni del movimento degli studenti negli anni ’60. Il sindacato studentesco è stato protagonista di numerose proteste: da quella contro la guerra in Corea alla questione delle basi americane sul suolo giapponese sino alle grandi manifestazioni di protesta del 1968.

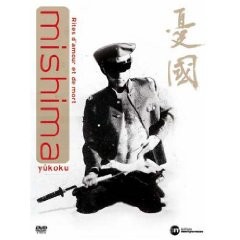

La lotta anti-ANPO giunse al culmine il 15 giugno 1960, quando all’Università di Tokyo la studentessa Michiko Kanba fu uccisa in uno scontro nei disordini con polizia di fronte al palazzo della Dieta. Sebbene la legislazione di ratifica del trattato fu approvata, la visita programmata in Giappone dal Presidente degli U.S.A. Dwight D. Eisenhower fu cancellata, e Kishi si dimise. Le sommosse stimolarono la sua fantasia e lo spinsero a scrivere nel 1960 ‘’Yukoku’’ (Patriottismo), racconto letterario e civile che lo introdusse nell’estrema destra sullo sfondo della Rivoluzione Conservatrice del 26 febbraio 1936 quando a NI NI Roku il movimento dei giovani preparò l’insurrezione, di una parte dell’esercito, contro il sistema asservito agli interessi dell’alta finanza, per promuovere l’autentica restaurazione imperiale. Una ventina di giovani ufficiali occuparono la zona dei ministeri adiacente il palazzo imperiale riuscendo ad assassinare delle personalità del mondo politico finanziario che comparivano sulla loro lista nera. Chiesero le dimissioni del governo, considerato traditore, l’avocazione di tutti i poteri militari da parte dell’Imperatore, una grande restaurazione Dhwa. Il proclama fu respinto da Hiro Hito, influenzato dagli ambienti finanziari contro cui insorsero i giovani ufficiali presi dal loro viscerale amor di Patria. L’Imperatore ordinò all’esercito di reprimere la sedizione e dichiarò gli insorti ‘’traditori’’.

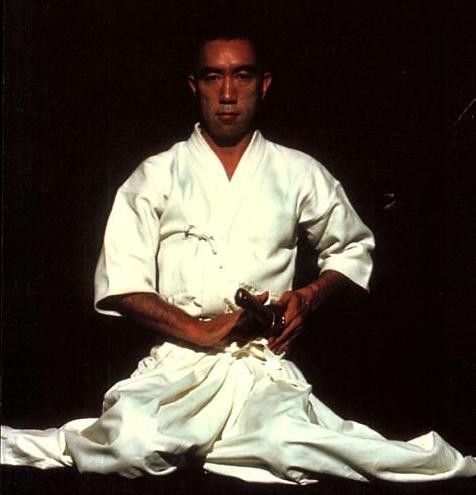

Gli ufficiali si arresero senza opporre resistenza. Due di loro fecero seppuku, sedici furono condannati a morte nel nome dell’Imperatore che volevano sottrarre al condizionamento dell’alta finanza. La vicenda del protagonista di ‘’Yukoku’’, un giovane tenente della guardia imperiale tenuto all’oscuro, dai colleghi, dell’insurrezione preparata, perché sposo, da pochi mesi, di una giovane donna di rara bellezza. Allo scoppio della rivolta fu convocato d’urgenza dal suo comando, ma, preferì disertare ed uccidersi invece che sparare ai suoi camerati che si erano’’ammutinati’’ per la Patria e per l’Imperatore. La moglie si suicidò con lui, dopo un amplesso appassionato: l’ufficiale seguendo l’antico rito dei samurai, la donna conficcandosi un pugnale in gola. Eroismo e morte eroica ricorrevano anticipando, lo scenario della fine dello scrittore. Dal racconto Mishima trasse nel 1965 un film che diresse ed interpretò. Poi scrisse, ancora ispirandosi al fatto di NI NI Roku, il dramma ‘’Il crisantemo del decimo giorno’’ (1960) e l’elegia ‘’La voce degli spiriti degli eroi’’ (1966) in cui il motivo conduttore era il perché l’Imperatore fosse dovuto divenire un comune mortale. Mishima descrisse una cerimonia shintoista immaginaria in cui si richiamavano le anime dei giovani ufficiali e dei kamikaze.

Gli uni rimproveravano all’Imperatore il rifiuto di sanzionare la loro insurrezione del febbraio ’36, gli altri di aver tradito la loro fede ed il loro sacrificio quando aveva accettato il nungen sengen, la dichiarazione di rinuncia alla sua natura divina imposta dagli americani. Con queste tre opere, raccolte in un volume nel 1970, Mishima mosse una dura critica all’Imperatore e si guadagnò l’antipatia di una certa destra, oltre che l’amicizia scontata dell’estrema sinistra. Tokyo fu migliorata per le Olimpiadi estive del 1964, nuove autostrade e del shinkansen (treno proiettile); trasformazioni della società libera, il popolo si illudeva che le colpe degli anni di guerra potevano essere dimenticate. La scena artistica esplodeva: una nuova generazione di cineasti, l’iconoclasta e radicale Nagisa Oshima, nei film ‘’Seishun Zankoku Monogatari’’ (Storia crudele della gioventù) e del ’69 ‘’Shinjuku Dorobo Nikki’’ (Diario del ladro di Shinjuku), i temi del giovane amore e della violenza, descrivendo quelli come le ribellioni contro la stabilità; soffocando la vecchia generazione, che aveva fallito in Giappone.

Masaki Kobayashi, nella sua monumentale trilogia di 9 ore, ‘’Ningen no Joken’’ (La condizione umana) del 1959-’60, descriveva la vera storia della guerra ed il suo effetto sui forzati a combatterla. La cosiddetta angura (movimento teatrale underground). Lo splendido Juro Kara, commediografo, artista in un’enorme tenda rossa, ridefinì il rapporto tra attore ed audience, ed elevò un nihilismo poetico. Minoru Betsuyaku scrisse la sua migliore opera, ‘’Zo’’ (Elefante), la storia di un sopravvissuto ad Hiroshima che vuole che il popolo giapponese non dimentichi. Shuji Terayama creò metaforicamente lavori drammatico surrealistici nel suo spazio Shibuya, Tenjo Sajiki, raccolse telespettatori nel suo giro d’Europa. Il fotografo Moriyama Hiromichi (Daido), designer grafico freelance a Osaka, usò il nuovo Giappone come soggetto centrale del suo lavoro. Il cambiamento radicale e vertiginoso del modello di società isolata e tradizionale in pratiche contemporanee, il paradosso di una cultura che considerava la trasformazione liberatoria e sconvolgente, scioccante ed irresistibile. Nel ’60 studiò fotografia con Hosoe Eiko a Tokyo e nel collettivo in scioglimento di fotografi VIVO.

Nel ’62 tramite Hosoe incontrò Mishima, di cui fu avido lettore, senza condividerne l’ideologia politica che in parte si rapportò agli interessi fotografici di Daido. Espressionista, con un erotismo intenso e oscuro ed un’inclinazione verso la drammaticità, comprese i conflitti nella società giapponese, l’accettazione della cultura occidentale dei vincitori e la ricerca di un’identità giapponese separata orgogliosamente, conflitti riecheggiati in Mishima. Daido fondeva i due mondi di Mishima: società convenzionale, proibito e tragico, usando il linguaggio popolare e diretto della fotografia. A Zushi, sobborgo di Tokyo, vicino alla base navale americana di Yokosuka, dove scattava foto istantanee nella base, con l’amico Nakahira Takuma, fotografo editore della rivista ‘’Gendai no me’’ (L’occhio moderno). Un saggio fu dedicato alla base americana di Yokosuka, importante per le sorti della guerra in Vietnam, conflitto che alimentò i sentimenti antibellici della sinistra e del movimento studentesco. Lo spirito di ribellione che spezzava i legami con la tradizione, gli ideali di democrazia e modernità.

Mentre il suo dominus Tomatsu Shomei era critico verso l’invasione della cultura americana in Giappone, senza novità e liberazione, ma con tratti sinistri e minacciosi; Daido vedeva nell’americanizzazione trasformazioni individuali, da outsider, il mondo enigmatico del teatro come vita, o Giappone come teatro. Intensificò la sua amicizia con Nakahira, intellettuale marxista vicino ai movimenti rivoluzionari studenteschi, che aveva fondato la rivista ‘’Provoke’’ nel ‘68 e lo aveva introdotto in un’atmosfera di ideali politici ed esistenziali di sinistra, che si riflessero in immagini scure, inquiete e incerte.

Nel 1967 con Yasunari Kawabata, Jun Ishikawa, Kobo Abe, Mishima firmò il manifesto contro la ‘’Rivoluzione culturale’’ cinese. Mishima in un’intervista al Sunday Mainichi nel marzo 1968, ribadì le proprie convinzioni riguardo all’Imperatore. Il kokutai, il sistema nazionale aveva cessato di esistere in conseguenza del nungen sengen dell’Imperatore. Da ciò il marasma morale postbellico. Ideale plasmato nell’ ‘’Amore per la naturalezza, gli dei nell’ideale, il culto del passato, cerimonie e cortesia come regole di condotta, nella difesa della bellezza, nella visione poetica del mondo’’. Mishima nel suo saggio ‘’Tate No Kai’’ sulla rivista inglese ‘Queen’ scrisse sulla Costituzione pacifista, di essere stanco dell’ipocrisia del dopoguerra giapponese, dato che la Costituzione pacifista era stata usata come alibi politico sia da destra che da sinistra, non credeva che ci fosse altro Stato in cui il pacifismo fosse sinonimo di ipocrisia. In Giappone il modo di vita onorato era quello di una vita senza pericoli, un po’ sinistrorso dei pacifisti e dei sostenitori della non-violenza. L’esagerato conformismo di tali intellettuali convinse Mishima che tutti i conformismi erano una iattura e che gli intellettuali avrebbero dovuto condurre un modo di vita pericoloso.

L’influenza degli intellettuali e dei salotti socialisti si era sviluppata in modo assurdo e ridicolo. Intimavano alle madri di non dare ai propri bambini giocattoli come armi da fuoco e consideravano militaresco mettersi in fila e numerarsi ad alta voce col risultato che i bambini si radunavano in modo sciolto e sfibrato come un gregge di deputati. L’azione del gruppo del Tate-No-Kai fu un atto simbolico per avviare il processo di revisione della Costituzione e la trasformazione del Jieitai in un legittimo esercito nazionale. Il fallimento apparente di tale tentativo segnò la cesura tra due mondi della Destra giapponese: quella controrivoluzionaria degli anni sessanta e quella, più autentica, nuova e radicale degli anni settanta ( Shin-Uyoku). Il Tate-No-Kai fu concepita come struttura di attacco: centinaia di uomini lottavano a mani nude contro gli studenti dello Zengakuren. Il discorso golpista supponeva la morte dell’orda di ultra sinistra e obbligare i militari ad attuare, ristabilendolo, il codice d’onore ed abolendo i costumi occidentali. Il prodursi nel 1969 di una delle più gigantesche e violente manifestazioni dell’ultra-sinistra, disciolta dagli antisommossa senza provocare una vittima, fece comprendere che tal progetto doveva avere interesse: l’imperatore non era indifeso, aveva i ‘’grigi’’ locali.

L’associazione non partecipava alle dimostrazioni di piazza ma si teneva pronta per ogni evenienza ad uno scontro decisivo con i nemici del Giappone, anche se dipendeva dal denaro e dai fondi ricavati dai diritti d’autore che Mishima percepiva dalle vendite dei suoi manoscritti. Nel 1968 Mishima era stato invitato ad un raduno della destra radicale per un dibattito, criticava il conformismo, specie quello di sinistra, scegliendo un’esistenza avventurosa, contro gli intellettuali effeminati ed il socialismo da salotto dell’èlite intellettuale. Conservava l’inclinazione militarista ed ultranazionalista dell’anteguerra. Lo spirito del samurai era estinto, perchè antiquato rischiare la propria vita per un’ideale. Prevaleva il mercantilismo liberale filoamericano, perciò gli studenti affrontavano violentemente gli intellettuali per difendere le idee ma era troppo tardi. I disordini studenteschi nelle università e nelle scuole superiori nipponiche ricordavano a Mishima gli scontri con i filosofi Sofisti, antagonisti di Socrate, che isolarono i giovani dell’agorà (piazza) che si era rivoltata. I giovani e gli intellettuali avevano il compito di vivere tra ginnasio e agorà per difendere la propria opinione con il corpo e le arti marziali oltre lo scambio delle opinioni. La strategia militare dell’invasione indiretta, la lotta ideologica finalizzata da una potenza straniera, la contesa tra chi violava l’identità nazionale e chi la difendeva; la lotta popolare sotto forma di nazionalismo o di combattimento delle milizie irregolari contro l’esercito regolare.

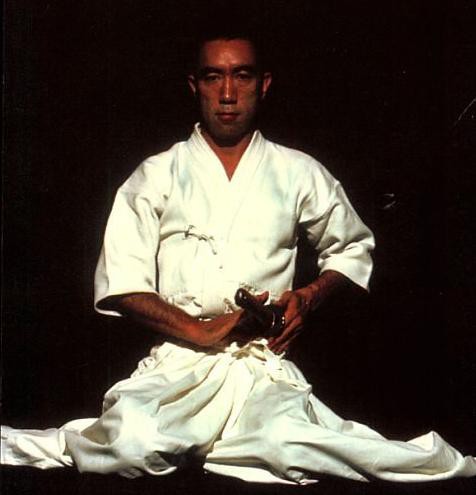

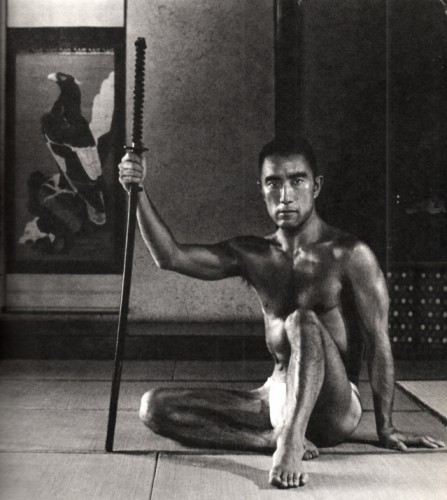

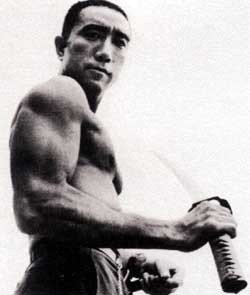

Nel luglio 1968, Mishima fu ricevuto dal ministro delle finanze Fukuda, suo ex compagno di università, cui espose un piano di riarmo militare e spirituale, fondato sulla tradizione patriottica e sull’esempio dei samurai. Fu deluso, mentre il Ministro della Difesa nazionale lo invitò a partecipare a grandi manovre. Nell’agosto divenne IV° Dan di Kendo e conobbe il venticinquenne Masakatsu Morita. Nel ’69 con 45 studenti Mishima effettuò un’esercitazione militare nel campo di Go Tenba. Si sottopose alle lezioni di Iai ed in tre mesi ottenne il grado di primo Dan, mentre in aprile partecipò ai campionati mondiali di Kendo, karatè, arti marziali, culto delle armi, azione, ardimento degli antichi samurai, preparandosi ad un’eventuale ipotetica lotta armata.

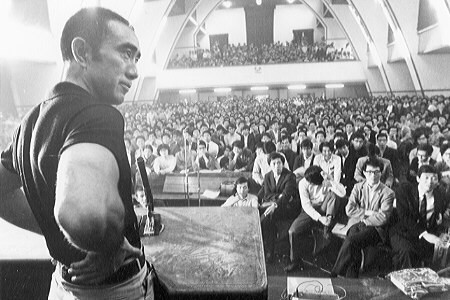

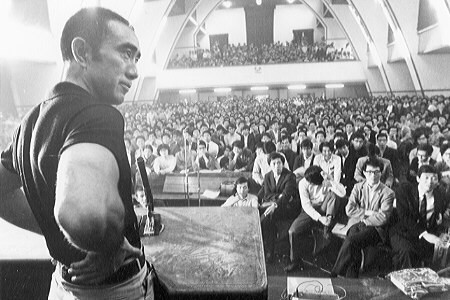

Il 13 maggio 1969 Mishima fu invitato all’Istituto di Cultura Generale all’università di Tokyo, presso la città universitaria di Komaba, ad un dibattito sulla terra madre, organizzato dal movimento studentesco di estrema sinistra Zenkyoto, rifiutando la protezione della polizia e dei suoi cadetti del Tate No Kai, insultando i suoi ospiti. Prese coraggio: davanti agli stessi studenti che avevano già dimostrato, prendendo degli ostaggi. Il giorno del dibattito, comparve all’entrata della sala, da solo. La sua sola protezione era il haramaki tradizionale, la lunghezza del panno di cotone fasciata strettamente intorno allo stomaco per deviare la spinta della lamiera di un ipotetico assassino. Nella sala duemila studenti stavano ascoltando la discussione. All’entrata vi era un manifesto che annunciava il dibattito, con una caricatura di Mishima come ‘’gorilla moderno’’. Mishima durante il suo dibattito con gli allievi di Zenkyoto indicò: ‘’ero nervoso al momento come se stessi entrando nella tana del leone, ma io l’ho goduta molto, dopo tutto. Ho trovato che abbiamo un mucchio di cose in comune – un’ideologia rigorosa e un gusto per la violenza fisica, per esempio. Sia loro che io rappresentiamo oggi la nuova specie nel Giappone. Ho conservato la loro l’amicizia. Siamo amici fra cui v’è un recinto di filo.’’

La conversazione fu nel complesso pacifica, sia pur interrotta da fischi ed esclamazioni di dissenso, Mishima espose le sue osservazioni ed asserzioni di stima per il movimento studentesco, cercando di dirottarne l’attenzione sulla necessità di un ritorno alla Tradizione, intesa in senso impersonale, per vendicare l’onore della figura dell’imperatore, della patria e del popolo nipponico nella decadente e corrotta società consumistico-liberale del Giappone yankeezzato. All’università di Tokyo Mishima affrontò coraggiosamente gli studenti in rivolta, nel tentativo di incontrare il rettore, tenuto prigioniero. Mishima era l’unico scrittore di ‘’estrema destra’’ in Giappone, mentre i professori universitari, gli studenti ed il mondo dell’editoria erano vicini al Partito Comunista Giapponese o segretamente si imboscava nelle istituzioni. Appellandosi alle tradizioni tradite, Mishima incitò gli studenti a risvegliare l’antico orgoglio dei guerrieri per i valori tradizionali che il processo di modernizzazione aveva cancellato. Il fanatismo, la ricerca dell’estetica della morte tragica, doppio suicidio per amore e follia, divennero un ossessione dominante, parabola tipica della tradizione Zen. Mishima non fu fascista o imperialista, ma lealista e nazionalista di estrema destra. La fedeltà al proprio Signore o Shogun (generale) dei cavalieri (Daymos o Signori) della nobiltà guerriera in epoca feudale nel XII secolo, strumenti di potere degli Shogun fino alla restaurazione imperiale Meiji del 1868, dopo la sconfitta, conseguente combattimenti secondo ferree regole di lealtà ed onore del codice d’onore dei guerrieri Bushido, qualora fossero in procinto di essere catturati, si davano la morte.

L’azione significava espiare, riparare, un esame di coraggio psichico ed una forma, degna di rispetto. Il guerriero Bushi, dopo una formazione psicologica del samurai, accettava la morte liberamente come scelta di un’azione più nobile e bella dell’essere umano. Nei secoli successivi l’atto fu comandato dai superiori dell’esercito nipponico a chi violava gli ordini o tradiva. Presso gli ufficiali, significava auto immolarsi per una causa superiore; come, poi, i piloti dei bombardieri dei caccia ‘’zero’’ giapponesi che si gettavano in picchiata sulle navi da guerra, durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, i Kamikaze, (‘’Vento degli dei’’, termine derivato dal tifone che salvò il Giappone dall’invasione della flotta mongola, affondandola, nel 1821), esempio dell’idea fissa di eroismo nella guerra del Pacifico. La purezza, l’ardimento, il sacrificio di giovani corrispondevano a modello leggendario di eroe, ed il loro fallimento e la loro morte li trasformava in autentici eroi. Scrivevano poesie e si equiparavano a maestri di spada, gareggiando fra loro per il primato nel combattimento ravvicinato uno contro uno, facendo gare di merito per ricevere onori massimi. Lo spirito dei samurai era corrotto e deformato a causa della debolezza militare delle forze armate giapponesi.

Un proverbio giapponese, estrapolato dal ‘’Mutsuwaki’’, cronaca di guerra di un autore sconosciuto (1051-1062), ammonisce che ‘’Il valore della vita, nei confronti del proprio dovere, ha il peso di una piuma’’. Il pilota kamikaze sull’attenti recitava la massima del ‘’Mutsuwaki’’: ‘’Adesso abbandono la mia vita, per la salvezza del mio Signore. La mia vita è leggera come la piuma di una gru. Preferisco morire affrontando il nemico, piuttosto di vivere voltandogli le spalle’’. Il Corpo dei kamikaze ha rappresentato un fulgido esempio di sprezzo della morte, l’incarnazione degli alti valori morali dei Samurai, per la Destra giapponese quella che fomentava ed auspicava un ritorno alle tradizioni del paese, imbarbarito dall’occidentalizzazione.

Nel 1938 fu decretata la legge per la mobilitazione nazionale e due anni dopo, il 27 settembre, fu concluso tra il Giappone, la Germania e l’Italia il Patto Militare tripartito, detto ‘’Ro.Ber.To.’’ (Roma-Berlino-Tokyo). Tutte le fazioni di destra si erano unite ed il paese fu avvolto in fervori nazionalistici, nel culto del Divino Imperatore, nell’ultrapatriottismo e nel militarismo. Non solo il popolo giapponese, con la sua educazione confuciana ed il culto di antica data per qualsiasi modello guerriero, non tentò nessuna seria resistenza al nuovo sistema, ma si mostrò ebbro di questo ideologico sakè vecchio e nuovo.

Le organizzazioni politiche di destra usarono, fin dai tempi bellici, i piloti kamikaze, come simbolo di un Giappone militaristico, colonialista ed estremamente nazionalistico, ultra-nazionalistico; la maggior parte dei giapponesi odierni, vedono il soggetto con ignoranza e come un falso stereotipo, commentandolo con toni negativi e di scarsa simpatia. Il Fascismo giapponese non fu eguale al Fascismo italiano o al Nazionalsocialismo tedesco, ma peculiare per il differente ‘’modus cogitandi’’ nipponico. Per designare questo periodo impregnato di totalitarismo si preferiva usare i termini ‘’Nihon-shugi’’ (Giapponismo, termine vago utilizzato da fonti nazionalistiche per enfatizzare l’unicità e superiorità di ciò che è politica, cultura e società giapponese) e ‘’Tenno-Sei‘’ (Sistema Imperiale o ‘’Fascismo Tenno Sei’’ o Fascismo militarista’’). Lo studioso F. Mazzei: ‘’la nascita del fascismo giapponese appare un fatto più naturale o per meglio dire ‘’meno patologico’’ che non in Italia e in Germania’’.

I capi nipponici avevano una istruzione formale ‘’top’’conseguita in università imperiali e/o Accademie Militari Imperiali; erano ‘’drogati’’ unicamente di devozione al loro Imperatore/Dio. Per i piloti kamikaze si addice il motto inscritto sulla lapide in ricordo della battaglia africana di El Alamein in Egitto: ‘’Mancò la fortuna, non il valore’’, che conta in positivo per il culto per la bellezza della sconfitta. Durante il Regno dell’Imperatore Showa, (1926-‘45), Hiroito, Principe della Corona, l’esercito divenne la vera autorità, la presenza dell’Imperatore era quella di un Dio e la Sua fu una figura più religiosa che politica. Nelle poesie ‘’Haiku’’ scritte dai piloti kamikaze, l’Imperatore era nominato alla prima riga.

La struttura sociale e gli schemi di pensiero ed azione dei secoli precedenti dominati dai guerrieri storici giapponesi non si estinsero dopo il 1945, anzi perdurarono sotto altre forme, nel governo, nel mondo affaristico capitalista, nel sistema educativo, nella vita sociale, con la teoria de’ ‘’Il libro dei Cinque anelli’’ del samurai Myamoto Musashi, scritta nel XVII secolo, fondatore della scuola delle ‘’due spade’’. Mishima condivideva con l’estrema sinistra una forma di protesta contro l’americanizzazione cruenta ed il capitalismo del Sol Levante. In lui arti marziali, filosofia e spiritualità si fondevano permettendo all’individuo di raggiungere la perfezione nel Bushido.

Era fra gli ultimi rappresentanti della cultura, della storia e delle tradizioni giapponesi e del culto dell’imperatore, con la battaglia combattuta fino alla morte. Un ponte, confronto/scontro fra due weltanschauung accomunate da un parallelismo di due sponde, due rive di un medesimo fiume vitale che come due rette in geometria all’infinito si incontrano, nel frattempo potevano esplorare insieme un percorso omogeneo o simmetrico nel reciproco rispetto per un futuro fulgore per entrambe. Mishima aveva speso appieno la sua vita in militanza sulla terra per épater le bourgeois, elevando alla massima potenza la sfida all’opinione pubblica che solo Tanizaki aveva tentato. Nelle università i giovani studenti erano in agitazione, specie a Tokyo, nel movimento studentesco in lotta, lo Zengakuren (non ancora Zengakuren Zenkyoto). L’azione politica dello Zengakuren presentava una sorta di tensione artistica. Gli studenti aderenti mescolavano i loro sogni infantili al mondo degli ideali e della politica. L’insoddisfazione, da cui nasce anche l’arte, è comune a ogni rivoluzione, anche se coronata da successo.

La rivoluzione o risolvere con metodi violenti i problemi in cui il popolo si dibatteva a causa delle contraddizioni della società, sognava un ordine ideale, da instaurare dopo la rivoluzione. La passione rivoluzionaria esigeva l’esistenza di irrefrenabili tensioni vitali, di miseria, di terribili contraddizioni sociali di particolari condizioni contingenti. La figura dell’uomo politico ligio al mantenimento dell’ordine degenerò nel simbolo di un tedioso e grigio conformismo, privo di alcun attrattiva. La passione rivoluzionaria diede inizio ad un’azione violenta in un anarchismo caotico, non supportato dalla presenza di atroci contraddizioni sociali o di un’effettiva miseria.

La rivoluzione propugnata dagli studenti non era ispirata da alcun principio in grado di suscitare la simpatia delle masse. Quest’idea rivoluzionaria si propagava nel mondo, trascinando nel vortice della confusione e della rivolta ogni paese. La tendenza a proiettare nel mondo dell’azione concreta aspirazioni che andrebbero rivolte all’arte, incapace di soddisfarle, riverberando le sue inquietudini esistenziali sulle angosce della società; saggia la vita producendo artificialmente uno scontro con la morte, a testimoniare tali esigenze con un’azione di lotta. Una simile artificiosa condotta politica non si limitava al nazismo tedesco ma si era diffusa nel mondo. La trasformazione politica dell’arte, la metamorfosi artistica della politica. Se l’arte è un sistema innocente, l’azione politica ha come suo principio base la responsabilità. L’azione politica è valutata in base ai risultati, è ammesso un movente egoistico ed interessato, purchè conduca a splendidi risultati; al contrario un’azione ispirata a un principio etico, che approdi ad un esito atroce, non esime chi l’abbia compiuta dall’obbligo di assumersi le proprie responsabilità. La situazione politica moderna ha introdotto nella sua sfera d’azione l’irresponsabilità dell’arte, riducendo la vita ad un concetto fittizio; ha trasformato la società in un teatro, il popolo in una massa di spettatori televisivi, producendo la politicizzazione dell’arte; l’azione politica non assurge all’antico rigore della concretezza e della responsabilità.

Le battaglie di fronte alle barricate nell’edificio Yasuda, all’Università di Tokyo, suscitarono l’interesse di una moltitudine di telespettatori, stanchi del solito sceneggiato. Uno spettacolo in cui gli attori scrissero sui muri ‘’Moriremo magnificamente’’, ostentando risolutezza all’atto estremo, ma non morirono, si arresero alla polizia. Nel moderno Giappone ci si adattava ai criteri della maggioranza senza vita militare, sopravvivendo all’iter per la formazione di casa e famiglia.

Lo Zengakuren radicalmente si mostrava audace ed affrontava energicamente la polizia, che reagiva pacatamente. Nè coraggiosi veri né codardi. La vita si confrontava con la morte. La teoria dell’azione, che definisca il limite fra situazione normale e di emergenza. Una tensione spirituale continua nel corso degli eventi quotidiani, la tensione nell’attendere virilmente il pericolo, nel rispetto delle regole morali di etichetta. Gli studenti che partecipavano a dimostrazioni politiche e si opponevano al governo, benché si ribellavano al potere, esigevano nei reciproci rapporti un rigoroso rispetto delle differenze gerarchiche tra studenti di classi superiori e inferiori. Apprendevano che ovunque agiva il desiderio di potere, la volontà di affermare un dominio, s’imponeva un’etichetta, un codice di comportamento, seguendo il quale si accresceva la propria autorità. Etichetta o comportamento secondo buona educazione esaltava la virilità negli uomini, per obiettivo di conquista. Le regole velavano il radicale antagonismo tra i partecipanti per la vittoria. L’etichetta è la corazza che difende l’uomo vero. L’autocontrollo e le norme di comportamento esaltano la bellezza virile.

Esaltavano lo spiritualismo della filosofia dell’azione dei giapponesi. La sublimazione di un egocentrismo prossimo ad un super-Io nietzschiano nel seppuku, contro il Giappone annichilito e corrotto, inserito nell’inquieta ricerca dell’autentica vitalità della sua carriera, in cui vita e opera letteraria, aspetti inscindibilmente legati, spingendolo a definire i suoi ultimi anni come ‘’Fiume dell’azione’’, che con prosa, teatro e corpo convergevano nell’Universo Mishima. Lo spiritualismo giapponese disprezza il corpo, diversamente dall’edonismo materialistico americano. Mishima viveva in un punto equidistante tra due stereotipi estremi di due diverse civiltà. La passione è il contrario del piacere, nel sesso. Provoca sofferenze e rischi gratuiti; nei giovani il desiderio sessuale si trasforma in passione, mentre negli adulti diviene piacere. I moderni liberano il sesso dalla passione, il piacere richiede denaro.

Gli adulti erroneamente definivano i movimenti studenteschi dello Zengakuren come un’inevitabile conseguenza dell’abolizione delle case chiuse. Il movimento studentesco divenne sempre più estremista, essendo influenzato dalla Nuova Sinistra, effettuando manifestazioni violente, con il lancio di bombe incendiarie, occupava le università che chiudevano, lottava contro il coinvolgimento del Giappone nella guerra degli U.S.A. in Vietnam nel 1961, contro la corruzione dei funzionari delle università e la crescita della spesa per l’istruzione controllata. Nel 1968 l’imponente movimento partecipò alle proteste ed alle occupazioni universitarie e delle scuole secondarie superiori, essendo costituito da studenti, docenti, personale non docente, ricercatori universitari, assistenti universitari, alcuni professori di ruolo, costituendo la Commissione d’Interfacoltà di lotta, Zenkyoto. Vi furono pure attacchi e scontri violenti con la polizia all’ambasciata U.S.A., poi l’ala più estrema degli studenti formò l’Armata Rossa Sekigun-ha, organizzazione clandestina armata nata nel 1969 dalla fusione di quattro gruppi studenteschi della sinistra rivoluzionaria: Chukaku; Kuhohern; Kehin Ampo; Kakam aru. Di ispirazione maoista ed antiamericana, per la rivoluzione proletaria in Giappone e, poi, internazionale con la Nihon Sekigun nel 1971 o strettamente nazionale con l’Armata Rossa Unita o Rengo Sekigun, organizzazioni terroristiche.

Un nuovo modello sociale dal 1967; polemiche prosperarono ed incoraggiarono una consapevole comunità di cittadini; l’agitazione nel mondo aveva scosso il Giappone. La guerra in Vietnam fece detonare le dimostrazioni di massa. Ad ottobre 1967, uno studente fu ucciso all’Aeroporto Haneda durante la protesta Zengakuren contro la visita del Primo Ministro Eisaku Sato al Sud Vietnam. Nel 1968, 3000 lavoratori dimostrarono all’Aeroporto di Osaka contro l’uso militare americano delle strutture.

Da maggio 1968, più di un milione di persone marciarono a Parigi, il governo francese barcollava. Il governo Dubcek in Cecoslovacchia stava dando un volto umanitario al comunismo fino all’invasione dell’U.R.S.S. e allo strappo della facciata per sbriciolarla in agosto . Molte persone giapponesi riconobbero che, dal 1968, con un secolo trascorso dalla Restaurazione Meji, l’economia stava esplodendo, accompagnata da bizzarre predizioni di un Giappone diveniente n.1 nel mondo. La società giapponese si riformava con democratiche linee, creando un sistema di due partiti e una struttura di stato assistenziale. Il governo arco – conservatore di Eisaku Sato, rieletto nel febbraio 1967 e poi di nuovo nel gennaio 1970, diede il messaggio al popolo giapponese: mai tanto benessere.

La logica della classe dirigente pretese un ulteriore sacrificio dal popolo, la repressione continua della libertà individuale ed il bene sociale liberalizzato negli interessi di uno sviluppo industriale. Il collasso del sogno del 1960 di un più aperto e socialmente tollerante Giappone, scatenò le lotte interne al movimento studentesco. Il movimento stava soccombendo all’anarchia ed alla devastazione, poi il Giappone assunse un altro corso, incanalando un remissivo e conforme popolo nelle mani di un governo determinato ad arretrare ai ‘’buon vecchi tempi’’, quando l’orgoglio nazionalistico dominava la coscienza della nazione. La massa compatta e armata di lunghi bastoni di Zengakuren, studenti organizzati dell’estrema sinistra, resta un’immagine indelebile del carattere nazionale e di massa di quelle lotte sessantottine. Nel ‘70 erano organizzati in gruppi che poi lo stato smontò abilmente e fece sparire.

Un poderoso movimento studentesco, contadino e operaio, patriottico (Mishima), rosso e rivoluzionario, che nessun partito socialista e comunista riuscì a comprendere, contenere e guidare, combattè per oltre 20 anni, dalla fine degli anni 50 alla fine degli anni 70, per non immolarsi di fronte allo sfruttamento del lavoro intenso, ‘’sviluppo economico’’. Il Giappone era nel 1968 il paese della coscienza critica e delle manifestazioni ordinate in fila indiana. La società del dissenso si arrese quarant’anni fa senza ritrovare il filo del discorso.

La guerra in Vietnam, in quel periodo migliaia e migliaia di persone scesero in piazza a Shinjuku per protestare contro il passaggio quotidiano di treni che trasportavano armi che sarebbero servite per uccidere delle persone. Gli studenti rivoluzionari persero tutte le battaglie: l’inquinamento e la cementificazione completi del paese furono incoraggiati; venne aperto il famigerato aeroporto di Tokyo di Narita incaricato di bombardare il sud est asiatico palesemente e segretamente, le organizzazioni sindacali falcidiate, il partito liberaldemocratico andò al governo a vita. Il ’68 giapponese fu il più difficile da domare e cercò di spazzare via ciò. Immolarsi in cambio della fine di quell’osceno spettacolo, fu un estremo gesto artistico-metaforico di combattimento, diventato realtà. Il Giappone dei ribelli si sviluppò e la sua tragica fine venne dopo la sconfitta del movimento rivoluzionario in Asia, con una svolta autoritaria e terroristica di una parte del movimento nipponico della sinistra rivoluzionaria, lo Zengakuren.

Un movimento articolato e complesso, che anticipò lucidamente e di circa un decennio, il ’68 mondiale, come nel film di Nagisa Oshima ‘’Notti e nebbie del Giappone’’, che indicò nella generazione dei dirigenti formati dallo stalinismo, deviazionisti compresi, l’origine della malattia mortale del ‘’comunismo’’. Prefigurandone ambiziose e transnazionali ‘’lunghe marce’’; 112 università occupate ed in rivolta, migliaia di arresti, morti, feriti (da ambo le parti, ma era sempre una ad attaccare), battaglie campali cruentissime, di cui una avvenuta nei sotterranei della metropolitana di Tokyo. Attacchi alle stazioni di polizia. Scontri violenti. Bombe molotov. Fazzoletti sul viso e travi di legno in mano. Sovversione e rivoluzione, proteste.

Il 21 ottobre del 44° anno dell’era Showa (‘’Armonia illuminata’’), 1968, una dimostrazione pacifista, l’ultima prima del viaggio in America del Primo Ministro, fu soffocata dalle forze schiaccianti della polizia.

Centinaia i feriti e gli arrestati. Mishima ne fu testimone nel quartiere di Shinjuju (Tokyo); travestito da reporter della sezione domenicale del quotidiano di notizie ‘’Mainichi Shimbun’’, ne provò rammarico. La sua preoccupazione era di osservare se c’era stata ‘’escalation nelle armi che la parte di sinistra ha avuta a disposizione’’. Seguì la calca degli studenti per la via principale del distretto di Shinjuku, scorrente veloce avanti ed indietro per osservare le esplosioni di violenza che descrisse sui suoi notecards, fino alla residenza del primo ministro, che fu circondata. Mishima, coscientemente o non, limitò la sua comprensione delle questioni politiche e degli eventi; il fatto è che i suoi punti di vista erano poco relazionabili con la realtà che la politica stava ponderando. In tal modo capiva che non era possibile far cambiare la Costituzione. Il governo si era reso conto dei limiti delle forze dell’estrema sinistra, dalla reazione del popolo verso l’intervento della polizia, non dissimile a un coprifuoco, trasse la sicurezza di poter riuscire a controllare la situazione, senza la questione dell’emendamento alla Costituzione.

La polizia fu sufficiente a mantenere l’ordine pubblico e le strutture politiche. Contenere ed arginare questa energia rivoluzionaria per i politici era quasi impossibile leggi speciali furono promulgate dallo stato incapace di stare al passo coi tempi. Il 19 gennaio 1969, 850 poliziotti della squadra antisommossa munite di armi fino ai denti aveva respinto gli operai e gli studenti fuori dalla costruzione in cui erano asserragliati. Mishima aveva osservato con ammirazione il confronto/scontro per la determinazione degli Zengakuren. Ma quando il corso Yasuda cadde nelle mani della polizia senza la morte di neanche uno studente, fu disgustato ‘’Osservate e ricordate disse ai suoi cadetti, ‘’quando il momento finale è venuto, non c’era uno di loro che ha creduto in ciò che corrispondeva sufficientemente per lanciarsi da una finestra o per suicidarsi con la spada’’. Enfasi autodistruttiva. Fu un fenomeno imponente, rabbioso, energico, in Giappone come nel resto del mondo. Il Giappone aveva il suo gruppo di studenti radicali che dalle proteste pacifiche transitarono al terrorismo mentre al loro interno conducevano epurazioni sanguinarie, origine, sviluppo e tragica fine del movimento armato rivoluzionario in Giappone.

Nella grande ondata di mobilitazione spoliticizzata, non appartenente a nessun partito politico, nacquero vari gruppi rivoluzionari di ispirazione comunista, in contrasto fra di loro, la Sekigun-ha (Armata Rossa) di cui negli anni ’70 la società non capiva cosa fosse: una rotella impazzita ed armata dell’ingranaggio. Fusako Shigenobu, figlia di un professore di scienze militante di un gruppuscolo di estrema destra prima di aderire al Partito Comunista Giapponese, membro fondatrice della Sekigun-ha, nel 1971 sarebbe andata in Libano dove avrebbe fondato la Nihon Sekigun (Armata Rossa Giapponese), divenne il più famoso di questi gruppi radicali, legato all’etica samurai nel suo programma, autore di numerosi atti di terrorismo che durarono circa venti anni. Un movimento di protesta e di genuina rivolta trasformatosi in un massacro ed in una occasione perduta. Del gruppo internazionale, una parte dirottò un aereo e si spostò in Corea del Nord, un’altra parte si trasferì in Palestina e in Libano. Il governo giapponese spera di poter fare estradarne dalla Corea del Nord numerosi membri che vi hanno trovato rifugio.

Tale questione è al cuore delle difficoltà diplomatiche tra Pyongyang e Tokyo. In Giappone rimase la manovalanza del gruppo che si unì ad alcuni membri fuoriusciti dal partito comunista formando l’Armata Rossa Unita (Rengo Sekigun). Questo era il comune modus operandi dell’estrema sinistra di quegli anni, incluse le Guardie Rosse cinesi. Mori, Nagata, e i loro alleati seppero dare un indirizzo nipponico alla loro inquisizione interna; atti di bullismo verso di chi offendeva in qualche modo l’armonia (wa) del gruppo. Da questo immane confronto una cellula di emme-elle ultradogmatici formò una struttura clandestina istigata alla lotta armata, costola dell’Esercito Rosso Giapponese che, rapito un ministro, poi liberato, dopo il placet a negoziare il riconoscimento dell’avversario politico, in cambio della fine di ogni azione armata in patria, ottenendo lo scambio dei prigionieri e l’Armata Rossa spaccata in due, con, in parte, il proprio esodo internazionalista in Palestina. Tale parte andò a combattere in Palestina al fianco del PFLP, Fronte Popolare per la Liberazione della Palestina, di indirizzo marxista-leninista, introducendo l’opzione kamikaze che ha sinistre appendici attuali. Dall’Armata Rossa nacque l’Armata Rossa Giapponese che spostò il suo interesse a livello internazionale; comprendeva esponenti del mondo artistico giapponese quali i registi Koji Wakamatsu, fiancheggiatore, ed il surrealista Masao Adachi (Fukuoka 1939), scrittore ed ex membro dell’Armata Rossa Giapponese, assertore della sovranità delle masse, che leggeva autori sovversivi marxisti-leninisti o tradizionali come Mishima. Ci fu, poi, una propaganda dei media contro i movimenti studenteschi di sinistra.

Adachi soggiornò molti anni nei carceri libanesi ed israeliane, fu estradato ed agli arresti domiciliari in Giappone, dove vive da qualche anno in stato di semilibertà. Amici di Genet, novello Orfeo sui cui nuovi valori selvaggi: il male per il male, l’uomo delle metamorfosi capace di trasformare la sofferenza nel suo contrario, la sovversione superiore della scrittura. Mishima gli aveva dedicato un saggio nel ’56. Nel 1967 Genet in Giappone partecipò alle campagne antimilitariste contro l’attracco delle portaerei militari americane nel porto di Sasebo, si impegnò nelle manifestazioni per i contadini di Sanrizuka, protestò contro un progetto di esproprio delle terre, fu coinvolto negli scontri studenteschi, al fianco degli Zengakuren, verso cui Mishima provava una passione iconoclasta. Nel 1960 alcuni studenti avevano risvegliato la loro coscienza e si erano addentrati nel movimento studentesco dello Zengakuren per poi arruolarsi nella destra nipponica nazionalista, la Kadoka, che appoggiava la figura imperiale, riconducibile alla rivolta del 26 febbraio 1936. Nel movimento studentesco militavano anche elementi di estrema destra, che avrebbero preso una deriva terroristica o con un complesso atteggiamento psicologico.

Le autorità dell’ultra destra e gli ‘’amici’’ di Mishima in Parlamento, nelle grandi Zaibatsu, (concentrazioni industriali, commerciali o finanziarie), e nella Yakuza, mafia giapponese, si rivolgevano all’Occidente nella corsa al benessere economico. A fianco della polizia, i ‘’crumiri’’ che picchiavano gli studenti e gli operai dello Zengakuren erano degli Yakuza ed i basuzoku, teppisti motorizzati. Del resto Mishima parlava di sottotenenti dell’accademia militare, che sentendosi prima di tutto militari professionisti, aristocratici o meno, ufficiali o semplici militari, tecnici neutrali; qualora il comunismo fosse giunto al potere in Giappone, avrebbero continuato a svolgere senza problemi la loro attività nella costituenda Armata Rossa. Era la base dell’istruzione militare nell’Accademia militare.

Genet si lasciava alle spalle ‘’il mondo ebraico-cristiano’’. Giappone, Palestina e Marocco furono un fulcro nell’opera di continuo spaesamento di Genet, dalla fine degli anni Sessanta, dopo il suo incontro con il Maggio francese e con i palestinesi, il suo scontro con Sartre. Il materialismo ossessivo assunse la forza di un disperato misticismo, che accomunava Genet e Mishima, entrambi alla quiete di Andrè Gide. Legati da un’esistenza segnata dal rifiuto e da un’opera cresciuta sotto l’ombra del desiderio di morte, il sesso istituiva per loro un vincolo a cui si legarono, per tenere a bada la morte. Se Genet si liberò di Gide, Mishima non si liberò di Genet. Generiche le accuse di antisemitismo, di ‘’mistica del vuoto’’ o di ‘’estetica fascista’’ dallo storico psicologizzante Ivan Jablonka.

Mishima non fu il cantore romantico della bella morte antica, ma il profeta della rinascita spirituale. I detrattori di Mishima gli rimproveravano le simpatie verso la destra ed il culto della forza, l’essere il jolly dell’imperatore, il narcisismo, il suo nichilismo, di essersi procurato una morte senza senso, tra un’etica normativa ed il nulla. Nell’ottica tradizionale dell’antica cultura del Sol Levante, dei samurai, dei guerrieri dell’onore, il suo sacrificio fu il ‘’suicidio del guerriero’’ per il disgusto provocato dalla mancanza di vigore per l’integrità del Giappone contemporaneo rispetto al retaggio culturale. Un gesto estremo, espressione psicologica dello spirito tradizionale giapponese, che fece riscontrare un fascino dovuto al suicidio rituale. Artista del culto dell’onore, della bellezza, della morte sensuale ed eroica, usò la società mediatica e ne fu usato, divenendo mito, icona, emblema. Sacrificio supremo gettato in faccia all’abominevole modernità demistificatrice del mito, disprezzo delle forme del sacro, esaltando il pubblico di fronte al privato nel nome di valori spirituali della tradizione. La postmodernità è la ‘’via della ‘’mano sinistra’’ del tantrismo e della ‘’legge degli opposti’’, che non è destra né sinistra. Non è conservatrice né rivoluzionaria, contiene e nega la modernità, né rivendica lo spirituale del tempo né esalta l’impostura della modernità; non difende la leggenda del passato, né la modernità nella modernità.

L’eroe postmoderno è innovatore, attualizza l’arcaico, l’eterno, l’immortale nell’effimero, spirituale stadio di purezza. Creazione verso l’assoluto, Dio nell’inferno vitale terreno. Il mito della bella morte, la nobiltà della sconfitta che gridava al vento della storia l’estrema rivolta ideale di chi non si rassegnava a cavalcare la tigre di ogni intramontabile nozione di assoluto; quel volto contratto a pronunciare parole prive di senso contro la perdita dello ‘’spirito nazionale’’ e contro la ‘’condizione di vuoto’’ in difesa dell’ ‘’onore’’ e dell’ ‘’esistenza dello spirito’’. La forza del passato mostrava il volto peggiore, normativo, autoritario, un samurai esausto, stanco di lottare, incurante del ridicolo. Un blocco di marmo ultranazionalista e reazionario, simbolo e sintomo di reazione alla decadenza.

La dicotomia tradizione-moderno in quanto figlio del Giappone costretto a rinnegare il proprio passato ed a subire la cultura del vincitore. L’idea di Mishima esulava il patriottismo europeo, il suo culto per la figura dell’Imperatore era un’idea trascendente tipo quella di Julius Evola e le sue idee in materia di tradizione che non ad un comune nazionalista. Intervistato dal critico marxista Takashi Furubayashi, Mishima ribadì che nel mondo attuale la forza era denigrata, per cui l’etica di coloro che cercano di essere forti è disprezzata. ‘’Azione’’ sintetizzata nel suo pensiero ‘’desidero dare me stesso fino alla morte e, pur avendo la mia età, non essere da meno dei giovani che mi circondano’’.

Antonio Rossiello

22/11/2009

, is an excellent introduction to Mishima’s life and work. It is by far the best movie about an artist I have ever seen. It is also surely the most sympathetic film portrayal of a figure who was essentially a fascist, maybe since Triumph of the Will

.

, Raging Bull

, The Last Temptation of Christ

, and Bringing Out the Dead

. His other screenplays include Brian De Palma’s Obsession

, Peter Weir’s The Mosquito Coast

, and his own American Gigolo

. Other movies directed by Schrader include the remake of Cat People

and the brilliant Auto Focus

, a biopic about a very different sort of artist, Bob Crane. It is so creepy that I will never watch it again, even though it is a masterpiece.

.)

, Kyoko’s House, and Runaway Horses

, which are filmed on unrealistic stage sets in lavish Technicolor.

focuses on the author’s Nietzschean exploration of the role of physiognomy and will to power in the origin of values. Nietzsche believed that all organisms have will to power, even sickly and botched ones. In the realm of values, will to power manifests itself particularly in a desire to think well of oneself. A healthy organism affirms itself by positing values that affirm its nature. The healthy affirm health, strength, beauty, and power. They despise the sickly, weak, and ugly.

is loosely based on the burning of the Reliquary (or Golden Pavilion) of Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto by a deranged Buddhist acolyte in 1950. In Mishima’s story, the arson is committed by Mizoguchi, an acolyte afflicted with ugliness and a stutter. The acolyte recognizes the beauty of the Golden Pavilion, but also hates it, because its beauty magnifies his deformities.

to illustrate Mishima’s exploration of his own youthful nihilism. Short even by Japanese standards (5’1”), skinny, physically frail, Mishima envied and eroticized the bodies of healthier boys, an eroticism that Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask

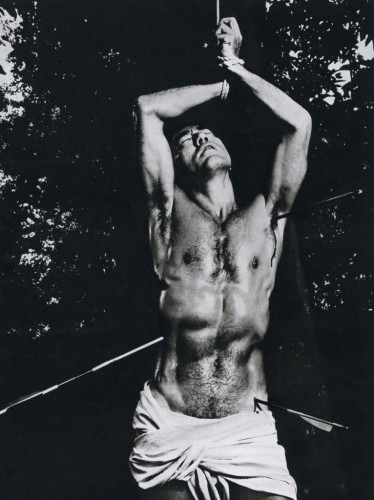

clearly indicates was tinged with masochistic self-hatred and sadistic fantasies of brutality and murder. (Mishima first became sexually aroused at a photograph of a painting of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian.)

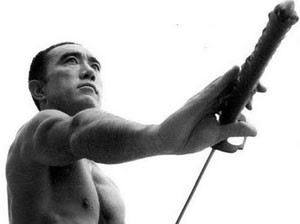

, however, is a look backwards, at paths Mishima could understand but could not follow. Unlike Kashiwagi, Mishima could not own his physical imperfections. Unlike Mizoguchi, he could not annihilate the ideal of beauty to feel good about himself. This left Mishima with only one choice: to remake his body according to the ideal of physical beauty. Thus in 1955, Mishima started lifting weights, with impressive results. He also took up kendo and karate.

(1963), in collaboration with photographer Eikoh Hosoe. Mishima also posed in Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan and OTOKO: Photo Studies of the Young Japanese Male by Tamotsu Yatō. His acting work was also an extension of this exhibitionism, as was his dandyism. When he wasn’t posing nude or in a loincloth, his clothes were exclusively Western. He dressed up like James Bond and dressed down like James Dean.

, his novel about Japan’s homosexual subculture, but Mishima’s widow refused permission. (She denied that Mishima had any homosexual proclivities.) But it is just as well. From what I can gather, Kyoko’s House is a far better novel than Forbidden Colors.

,” a short story about the aftermath of the “Ni Ni Roku Incident” of February 1936, an attempted coup d’état by junior officers of the Imperial Army who assassinated several political leaders. The officers wished the government to address widespread poverty caused by the world-wide Great Depression. The coup was cast as an attempt to restore the absolute power of the emperor, but he regarded it as a rebellion and ordered it crushed.

” in 1961. In 1965, he directed and starred in 28-minute film adaptation which he first released in France. The film of Patriotism

is erotic, chilling, and cringe-inducingly graphic (people regularly fainted when they saw it in theaters). In retrospect, it seems like merely a rehearsal for Mishima’s eventual suicide. The music, fittingly, is the Liebestod (Love-Death) from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. Mishima’s widow locked up the film after her husband’s death. After her death, it was released on DVD by the Criterion Collection. (Mishima also committed suicide on screen in Hideo Gosha’s 1969 film Tenchu!)

and also dramatizes a very similar episode from Runaway Horses

(1969), the second volume of Mishima’s The Sea of Fertility

quartet (1968–1970). The Sea of Fertility is a panorama of Japan’s traumatic crash course in modernization, spanning the years 1912 to 1975, narrating the life of Shigekuni Honda, who becomes a wealthy and widely-traveled jurist.

, set in 1932–1933, is the story of Isao Iinuma, a right-wing student who seeks the alliance of the military to plot a rebellion in 1932. The goal is to topple capitalism and restore absolute Imperial rule by simultaneously assassinating the heads of industry and the government and torching the Bank of Japan. The plot is foiled, but when Isao is released from prison, he carries out his part of the mission anyway, assassinating his target. The assassination, of course, is politically futile, but Isao feels honor-bound to carry out his mission. He then commits hari-kiri.

claimed that Japan under the Shogunate showed how we might retain our humanity at the end of history through an aristocratic culture that rested on the cultural ideal of a “purely gratuitous suicide.”)

, his commentary on the Hagakure

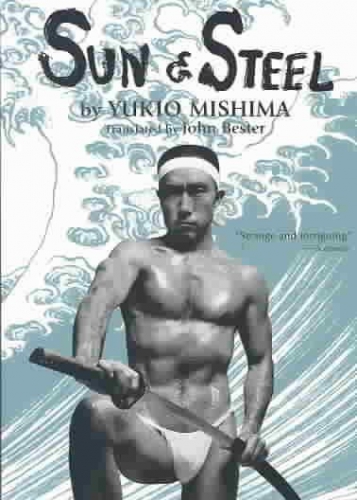

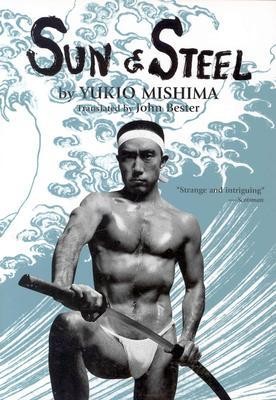

(literally, In the Shadow of the Leaves), a handbook authored by the 18th-century Samurai Tsunetomo Yamamoto. In 1968, Mishima published Sun and Steel

, an autobiographical essay about bodybuilding, martial arts, and the relationship of thought and action which also discusses ritual suicide. (In 1968, Mishima also published a play, My Friend Hitler

, about the Röhm purge of 1934. He was coy about his true feelings toward Hitler. In truth, he was more a Mussolini man.)

, paints a very bleak portrait of old age.)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

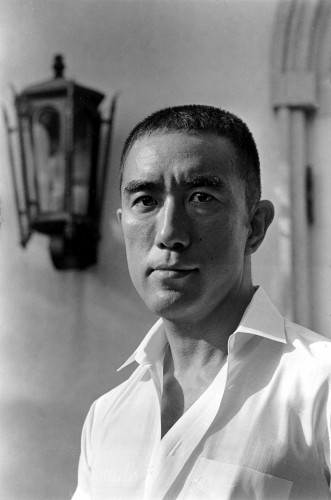

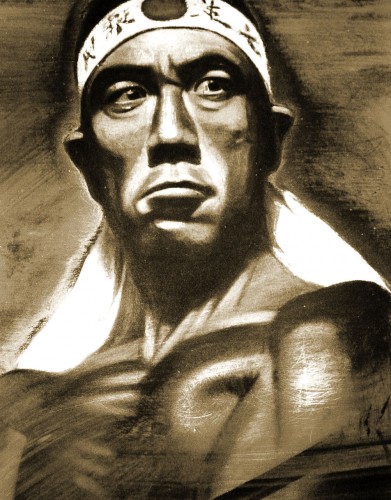

Mishima, nato nel 1925, era molto giovane durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale ma poté partecipare all’ultimo anno di guerra; era scusato. All’epoca deve esser stato ossessionato dall'”uomo d’acciaio”, perché il suo amico Hasuda, collega scrittore, afferma: “Credo che si debba morire giovani, alla sua età”. Hasuda fu fedele alla parola, perché si suicidò. Sembra che l’omosessualità possa anche aver tormentato Mishima, poiché in Confessioni di una maschera (1949) si occupa di emozioni interiori e passioni. Tuttavia, se Mishima conosceva bene la storia di molti samurai, allora avrebbe creduto che l’omosessualità fosse la forma più pura di sesso. Inoltre, molti leader del Giappone nel periodo pre-Edo ed Edo ebbero concubini maschi. Pertanto, Mishima si vergognò dell’etica cristiana arrivata in Giappone con la Restaurazione Meiji (1868)? Se no, allora molti “uomini d’acciaio” del vecchio Giappone ebbero relazioni omosessuali e questo andava inteso alla luce della realtà. Dopo tutto, la lealtà nel vecchio Giappone era per il sovrano daimyo e i compagni samurai. Pertanto, la compassione era ritenuta cosa per deboli, a causa della natura della vita. Non sorprende che forti legami maschili prendessero piede nella psiche dei samurai e tale realtà culturale sia all’opposto dell’immagine dell’omosessualità nel Giappone moderno, percepita per deboli. Il Wakashudo aveva diversi modi di avviare i ragazzi nel “vecchio Giappone” e nella mentalità dei samurai, le donne venivano viste femminilizzare gli uomini indebolendone lo spirito. Il sistema Wakashudo fu spesso abusato dal clero buddista per proprie gratificazioni sessuali, in passato. Tuttavia, il sistema dei samurai si basava sulla creazione di “un processo di apprendimento secondo un codice etico” impiantando lealtà e forti legami per cui, in tempi di difficoltà, i samurai rimasero attaccati all’istruzione ricevuta. Mishima, gonfiando i muscoli e dalle competenze marziali ben levigate, divenne l'”uomo d’acciaio”. Tuttavia, fu contaminato dalle pose femminili fusesi nel suo martirio. Posò volentieri di fronte alle telecamere e le immagini di San Sebastiano ucciso da molte frecce o del samurai che invoca il suicidio rituale, giocarono la sua psiche e il suo essere. Il mondo di Mishima era reale e surreale, perché potere e forza si fusero, ma avendo una natura femminile seppellita nell’anima. Mishima dichiarò: “Il tipo più appropriato di vita quotidiana, per me, fu la quotidiana distruzione mondiale; la pace è il più duro e anormale modo di vivere”. Pertanto, il 25 novembre 1970, si avverò ciò che Mishima era divenuto. Tale realtà si basava su visioni suicide, quindi il suo mondo illusorio sfociò in un fine violenta. Tuttavia, la verità di Mishima fu la fine violenta e caotica entro una realtà struttura. Dopo tutto, Mishima stilò dei piani successivi alla morte. Inoltre, Mishima si dedicò per tale giorno da anni, ma ora il tempo della recitazione era finito, in parte, perché ancora si agitava nel mondo dell'”ego”. Nel suo mondo illusorio il “sé” avrebbe agito collettivamente con forza, a sua volta generando “uno spirito” tratto dal sogno di Mishima di morte glorificata. Eppure, non era un soldato, dopo tutto aveva mentito, non avendo combattuto per il Giappone; quindi, la retorica nazionalista fu proprio tale e il 25 novembre fu più una”redenzione personale” che pose fine alla “dualità della sua anima”. L’uomo delle parole sarebbe morto nel “paradiso dell’estremo dolore”, perché l’ultima sciabolata che lo decapitò non fu netta, furono necessari diversi tentativi. Dopo tutto, non era un soldato, non era un samurai e lo non erano neanche i suoi fedeli seguaci. L’atto finale è la prova che i “sognatori” sono proprio ciò; quindi, il finale non fu una bella immagine di serenità, ma una scena “infernale stupida e di follia autoindotta”. Il mondo illusorio di Mishima non poteva cambiare nulla, perché non riusciva a riscrivere la storia. Sì, dopo di lui si poté riscrivere la storia e forse questa era cui Mishima anelava?

Mishima, nato nel 1925, era molto giovane durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale ma poté partecipare all’ultimo anno di guerra; era scusato. All’epoca deve esser stato ossessionato dall'”uomo d’acciaio”, perché il suo amico Hasuda, collega scrittore, afferma: “Credo che si debba morire giovani, alla sua età”. Hasuda fu fedele alla parola, perché si suicidò. Sembra che l’omosessualità possa anche aver tormentato Mishima, poiché in Confessioni di una maschera (1949) si occupa di emozioni interiori e passioni. Tuttavia, se Mishima conosceva bene la storia di molti samurai, allora avrebbe creduto che l’omosessualità fosse la forma più pura di sesso. Inoltre, molti leader del Giappone nel periodo pre-Edo ed Edo ebbero concubini maschi. Pertanto, Mishima si vergognò dell’etica cristiana arrivata in Giappone con la Restaurazione Meiji (1868)? Se no, allora molti “uomini d’acciaio” del vecchio Giappone ebbero relazioni omosessuali e questo andava inteso alla luce della realtà. Dopo tutto, la lealtà nel vecchio Giappone era per il sovrano daimyo e i compagni samurai. Pertanto, la compassione era ritenuta cosa per deboli, a causa della natura della vita. Non sorprende che forti legami maschili prendessero piede nella psiche dei samurai e tale realtà culturale sia all’opposto dell’immagine dell’omosessualità nel Giappone moderno, percepita per deboli. Il Wakashudo aveva diversi modi di avviare i ragazzi nel “vecchio Giappone” e nella mentalità dei samurai, le donne venivano viste femminilizzare gli uomini indebolendone lo spirito. Il sistema Wakashudo fu spesso abusato dal clero buddista per proprie gratificazioni sessuali, in passato. Tuttavia, il sistema dei samurai si basava sulla creazione di “un processo di apprendimento secondo un codice etico” impiantando lealtà e forti legami per cui, in tempi di difficoltà, i samurai rimasero attaccati all’istruzione ricevuta. Mishima, gonfiando i muscoli e dalle competenze marziali ben levigate, divenne l'”uomo d’acciaio”. Tuttavia, fu contaminato dalle pose femminili fusesi nel suo martirio. Posò volentieri di fronte alle telecamere e le immagini di San Sebastiano ucciso da molte frecce o del samurai che invoca il suicidio rituale, giocarono la sua psiche e il suo essere. Il mondo di Mishima era reale e surreale, perché potere e forza si fusero, ma avendo una natura femminile seppellita nell’anima. Mishima dichiarò: “Il tipo più appropriato di vita quotidiana, per me, fu la quotidiana distruzione mondiale; la pace è il più duro e anormale modo di vivere”. Pertanto, il 25 novembre 1970, si avverò ciò che Mishima era divenuto. Tale realtà si basava su visioni suicide, quindi il suo mondo illusorio sfociò in un fine violenta. Tuttavia, la verità di Mishima fu la fine violenta e caotica entro una realtà struttura. Dopo tutto, Mishima stilò dei piani successivi alla morte. Inoltre, Mishima si dedicò per tale giorno da anni, ma ora il tempo della recitazione era finito, in parte, perché ancora si agitava nel mondo dell'”ego”. Nel suo mondo illusorio il “sé” avrebbe agito collettivamente con forza, a sua volta generando “uno spirito” tratto dal sogno di Mishima di morte glorificata. Eppure, non era un soldato, dopo tutto aveva mentito, non avendo combattuto per il Giappone; quindi, la retorica nazionalista fu proprio tale e il 25 novembre fu più una”redenzione personale” che pose fine alla “dualità della sua anima”. L’uomo delle parole sarebbe morto nel “paradiso dell’estremo dolore”, perché l’ultima sciabolata che lo decapitò non fu netta, furono necessari diversi tentativi. Dopo tutto, non era un soldato, non era un samurai e lo non erano neanche i suoi fedeli seguaci. L’atto finale è la prova che i “sognatori” sono proprio ciò; quindi, il finale non fu una bella immagine di serenità, ma una scena “infernale stupida e di follia autoindotta”. Il mondo illusorio di Mishima non poteva cambiare nulla, perché non riusciva a riscrivere la storia. Sì, dopo di lui si poté riscrivere la storia e forse questa era cui Mishima anelava?

La deuxième des quatre œuvres issues de la collaboration de Teshigahara avec l’écrivain Kobo Abe, La Femme des Sables, est son long métrage le plus célèbre. C’est aussi certainement celui qui laisse l’impression la plus forte et la plus durable.

La deuxième des quatre œuvres issues de la collaboration de Teshigahara avec l’écrivain Kobo Abe, La Femme des Sables, est son long métrage le plus célèbre. C’est aussi certainement celui qui laisse l’impression la plus forte et la plus durable.

Chapter four, being the longest of the four chapters at about 110 pages, stands out as a relatively independent account of Mishima’s later years, dealing with both literature and political/ideological developments, leading to his failed coup, featuring his impassioned exhortation to the military servicemen and his ritual suicide by seppuku. This part covers the Mishima most familiar and interesting to Western readers. The chapter covers his body-building practices, his continued literary endeavors, consummated by the masterpiece The Sea of Fertility,his nominations for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and his increasingly active socio-political undertakings, including organizing his private militia troop, the Tatenokai (Shield Society), his serious and strenuous military training in Jieitai (Self-Defense Force), the post-war Japanese military — with the rather naïve aim of safeguarding the Emperor in concerted effort with the military in case of domestic unrest or even sedition at the hands of the leftist or communist radicals — and the events of this final day, November 25, 1970.

Chapter four, being the longest of the four chapters at about 110 pages, stands out as a relatively independent account of Mishima’s later years, dealing with both literature and political/ideological developments, leading to his failed coup, featuring his impassioned exhortation to the military servicemen and his ritual suicide by seppuku. This part covers the Mishima most familiar and interesting to Western readers. The chapter covers his body-building practices, his continued literary endeavors, consummated by the masterpiece The Sea of Fertility,his nominations for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and his increasingly active socio-political undertakings, including organizing his private militia troop, the Tatenokai (Shield Society), his serious and strenuous military training in Jieitai (Self-Defense Force), the post-war Japanese military — with the rather naïve aim of safeguarding the Emperor in concerted effort with the military in case of domestic unrest or even sedition at the hands of the leftist or communist radicals — and the events of this final day, November 25, 1970.

In Japan suicide has never been the taboo act that it traditionally is in the West. Since the advent of Christianity suicide in the West has been forbidden by the Church and often also by law. This taboo against suicide stems from Augustine who argued that life, being a gift from God, is not to be taken away, even by one’s own hand. This taboo was enshrined in law and continues to cast a dark shadow into modern times. As recently as 1969 a teenager was birched in The Isle of Man for attempting to commit suicide.[5] And it is still the case that official investigations into suicides will try their best to remain euphemistic about the cause of death:

In Japan suicide has never been the taboo act that it traditionally is in the West. Since the advent of Christianity suicide in the West has been forbidden by the Church and often also by law. This taboo against suicide stems from Augustine who argued that life, being a gift from God, is not to be taken away, even by one’s own hand. This taboo was enshrined in law and continues to cast a dark shadow into modern times. As recently as 1969 a teenager was birched in The Isle of Man for attempting to commit suicide.[5] And it is still the case that official investigations into suicides will try their best to remain euphemistic about the cause of death: In fact, Mishima had written a description of seppuku in gruesome detail some years earlier. In the short story, Patriotism, he describes a young officer who is unwilling to act against his former comrades who had taken part in the Ni Ni Roku rebellion. In order to maintain his honor, the officer commits seppuku:

In fact, Mishima had written a description of seppuku in gruesome detail some years earlier. In the short story, Patriotism, he describes a young officer who is unwilling to act against his former comrades who had taken part in the Ni Ni Roku rebellion. In order to maintain his honor, the officer commits seppuku: All of this leads many observers to conclude that the right wing nationalism that Mishima adopted in the 1960s, culminating in his formation of the Tatenokai and attempted coup d’etat, was another mask that he wore, one that provided him with a convenient pretext to commit the suicide that he had aestheticised and eroticised for so long. Whilst it would be foolhardy to try to identify the “real” motives of such a complex man, it is still possible to see that this argument is inadequate to the facts. One critic who follows this line of thought declares that Mishima’s suicide was, “the ultimate in literary irony.”[19] A rereading of the extract quoted above concerning the physical effects of performing seppuku should give appropriate context to thoughts of an ironic suicide. A person does not cut out his intestines as an act of literary irony.

All of this leads many observers to conclude that the right wing nationalism that Mishima adopted in the 1960s, culminating in his formation of the Tatenokai and attempted coup d’etat, was another mask that he wore, one that provided him with a convenient pretext to commit the suicide that he had aestheticised and eroticised for so long. Whilst it would be foolhardy to try to identify the “real” motives of such a complex man, it is still possible to see that this argument is inadequate to the facts. One critic who follows this line of thought declares that Mishima’s suicide was, “the ultimate in literary irony.”[19] A rereading of the extract quoted above concerning the physical effects of performing seppuku should give appropriate context to thoughts of an ironic suicide. A person does not cut out his intestines as an act of literary irony.

Yukio Mishima è un intramontabile della cultura mondiale, oggetto di ripubblicazioni a getto continuo, convegni di studio, rappresentazioni teatrali e altre forme di tributo. Un omaggio inconsueto ed inaspettato alla figura dello scrittore giapponese viene dal romanzo vincitore dell'ultimo Premio Urania, Lazarus di Alberto Cola (Mondadori, pp. 317, € 4,20).

Yukio Mishima è un intramontabile della cultura mondiale, oggetto di ripubblicazioni a getto continuo, convegni di studio, rappresentazioni teatrali e altre forme di tributo. Un omaggio inconsueto ed inaspettato alla figura dello scrittore giapponese viene dal romanzo vincitore dell'ultimo Premio Urania, Lazarus di Alberto Cola (Mondadori, pp. 317, € 4,20).  Le parole non bastano. Così parlò Yukio Mishima, e il 25 novembre del 1970 si uccise davanti alle telecamere col rito tradizionale del seppuku. Alle parole seguì il gesto e la scrittura debordò nella vita per compiersi nella morte. Il suicidio eroico di Mishima scosse la mia generazione, versante destro. Era il nostro Che Guevara, e sposava in capitulo mortis la letteratura e l’assoluto, l’esteta e l’eroe, il Superuomo e la Tradizione. Lasciò un brivido sui miei quindici anni. Poi diventò un mito a diciassette, quando uscì in Italia Sole e acciaio, il suo testamento spirituale. È uno di quei libri che trasforma chi lo legge; gustato riga per riga, non solo letto ma vissuto, come un libro d’istruzioni per montare la vita, pezzo per pezzo. Altro che Ikea, il pensare si riversava nell’agire. Le parole non bastano.

Le parole non bastano. Così parlò Yukio Mishima, e il 25 novembre del 1970 si uccise davanti alle telecamere col rito tradizionale del seppuku. Alle parole seguì il gesto e la scrittura debordò nella vita per compiersi nella morte. Il suicidio eroico di Mishima scosse la mia generazione, versante destro. Era il nostro Che Guevara, e sposava in capitulo mortis la letteratura e l’assoluto, l’esteta e l’eroe, il Superuomo e la Tradizione. Lasciò un brivido sui miei quindici anni. Poi diventò un mito a diciassette, quando uscì in Italia Sole e acciaio, il suo testamento spirituale. È uno di quei libri che trasforma chi lo legge; gustato riga per riga, non solo letto ma vissuto, come un libro d’istruzioni per montare la vita, pezzo per pezzo. Altro che Ikea, il pensare si riversava nell’agire. Le parole non bastano.

Yukio Mishima war sicherlich eine der schillerndsten, exzentrischsten und interessantesten Figuren, die je das Licht der literarischen Welt erblickten. Hierzulande erfreuen sich seine Werke wie Geständnis einer Maske, Patriotismus, Schnee im Frühling oder Liebesdurst großer Beliebtheit – dies jedoch zumeist innerhalb eines eher kleinen Zirkels. Man könnte also von einem „Geheimtip“ sprechen. Dabei dürfte dieser Mann bei weitem kein Unbekannter sein. International berühmt und sogar zwischenzeitlich im Gespräch für den Literaturnobelpreis gilt Mishima als einer der Exportschlager aus dem Land der aufgehenden Sonne.

Yukio Mishima war sicherlich eine der schillerndsten, exzentrischsten und interessantesten Figuren, die je das Licht der literarischen Welt erblickten. Hierzulande erfreuen sich seine Werke wie Geständnis einer Maske, Patriotismus, Schnee im Frühling oder Liebesdurst großer Beliebtheit – dies jedoch zumeist innerhalb eines eher kleinen Zirkels. Man könnte also von einem „Geheimtip“ sprechen. Dabei dürfte dieser Mann bei weitem kein Unbekannter sein. International berühmt und sogar zwischenzeitlich im Gespräch für den Literaturnobelpreis gilt Mishima als einer der Exportschlager aus dem Land der aufgehenden Sonne.